Among my many other activities these days, I'm working on a new book … or something like that.

That qualification reflects the uncertainty of the times. As volumes printed on paper evolve to newer media – at some point, a printed volume seems likely to become a luxury item – we're obliged to think about what constitutes a book in the digital age. I used to think I knew the answer, but I'm no longer remotely sure. Two recent events have not cleared things up. After listening to smart and well-informed speakers at a "Future of Publishing" panel in California late last year, as well as at last week's "O'Reilly Tools of Change for Publishing" conference in New York City, I found myself, if anything, less certain.

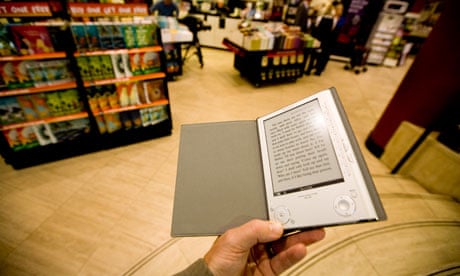

It was easy, not so long ago, to say, "This is a book, and this isn't." From the early Codex to hand-penned Bibles (created by "scribes"), Gutenberg's printing press through the late 20th century, a book was a collection of bound pages. But as has happened with other media forms, digital technology has blurred the lines we once took for granted.

On the internet, media formats easily cross boundaries – something we've all seen in recent times. In the news business, for example, what were once print-only newspapers now create videos, and television channels have added articles that could easily appear in print. Everyone is using new tools, such as map/sensor mashups, to create a vast variety of forms that are native to the online world. We can still identify a newspaper if it's dropped at our doorstep – and some of us still get the New York Times delivered on Sundays – but take it online and it's clearly something else.

The book's boundaries have moved as well, but not as far. It still functions as a linear, self-contained unit. It has a beginning, a middle and and end. It is unlikely that I can read it in one sitting, unless I'm on a particularly long plane ride, or so wrapped up in the text that I can't stop. In other words, a book still feels like the recognizable form of the past.

But I'm not at all trying to suggest that we should leave it there – and all kinds of creative people are finding ways to enhance the traditional book, with things like hyperlinks, embedded videos, games, conversations, etc. I used hyperlinks in my last book in lieu of most footnotes, and no one complained. I plan to go further, with videos and other material that I hope will deepen the experience without changing it too much.

The "Tools of Change" gathering featured some fascinating new services designed to help authors create for the online world first, with printed editions an afterthought (if that). For example, a system called Inkling Habitat, aimed at collaborations – a method I strongly believe will be a major trend in authoring. Inkling and Habitat put too many restrictions on authors for my taste, but they help point the way toward a robust future.

At some point, however, stretching boundaries becomes like stretching a rubber band. When it breaks, a rubber band has become something else, just an elastic length, which may have some uses, but won't work as a rubber band anymore. Maybe we'll need a new name for the trans- and multimedia forms that emerge in coming years, as people who are native to the digital world create things that would never occur to me or other authors who grew up with traditional books.

As is the case with news and entertainment media, the biggest changes to date are on the business side. Publishers, which had served as filter, manufacturer and promoter, are wondering why they exist in a world where the filtering can be done by the audiences and independent curators; where production and manufacturing are easier than ever to farm out (and mostly unnecessary with digital publishing); and where authors have taken on their own promoting. (You'll note that I didn't mention editing; publishers have all but abandoned that function, in any case.)

The main problem today with online books is a lack of standardization and portability, made worse by restrictions that booksellers make with Digital Rights Management and other techniques. I hope publishers don't go the way of Hollywood, and it's heartening to see some smarter publishers drop DRM altogether. It's what the customers want, after all.